by Kate Redmond

Oil Beetle Adventures

Greetings, BugFans,

When the BugLady was walking at Riveredge towards the end of September, she came to a fork in the trail and thought “if I go left, I’ll get back to the car faster, but if I go right, I’ll see something good.” So she did, and she did.

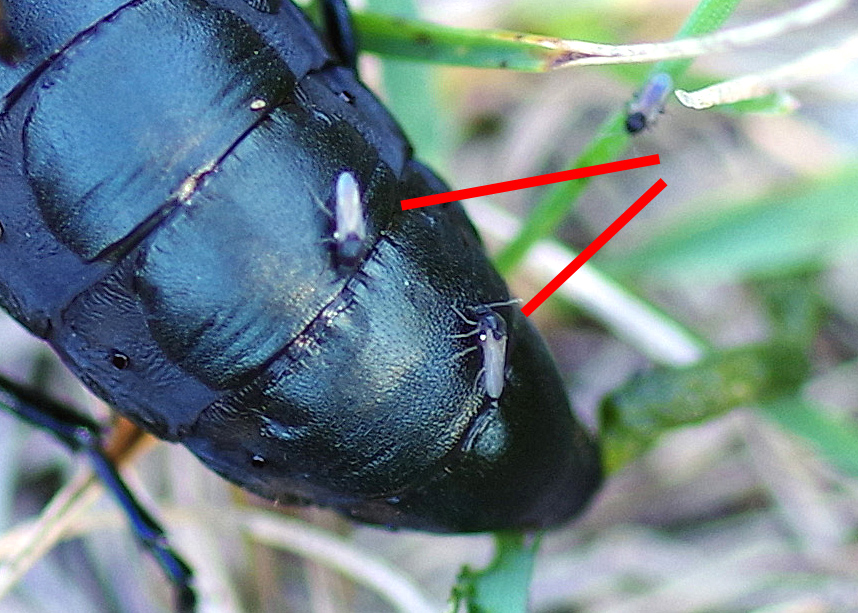

Along a 15 foot stretch of trail, she found a half-dozen Oil beetles in the grass (including one pair in flagrante delicto). She suspects that some of the motionless females may have been ovipositing. And then she looked closer.

Oil beetles, which are blister beetles (family Meloidae) in the genus Meloe, are odd-looking beetles – inky blue-black, soft, and bulbous (“bloated,” said one source; “like a black clove of garlic,” said another), with astonishing antennae. Their elytra (wing covers) are very short, because they actually have no hind wings to cover. The name “Oil beetle” comes from the oily drops of haemolymph (bug blood) (aka hemolymph, but the BugLady loves the British spelling) that ooze from their joints when they’re alarmed https://bugguide.net/node/view/408611/bgpage. Look, but don’t touch – the oil contains cantharidin, which is one of their Super Powers. We have met blister beetles in previous BOTWs – here’s Blister Beetle 101 https://uwm.edu/field-station/bug-of-the-week/blister-beetle/.

It’s a genus that has somewhat northern proclivities, with many species present across Canada.

They are, oddly, measured from the front of the head only to the far point of the elytra, rather than to the end of the (often-distended) abdomen. Females may be as long as 1 ½” and males are smaller.

When a young Meloe beetle’s fancy turns to love, he finds a female, climbs aboard, and rubs her antennae with his, releasing a pheromone that calms her. Bugguide says, “In males of some species mid-antennal segments are modified, and the c-shaped ‘kinks’ (antennomeres V–VII) grasp female antennae during pre-mating displays.” He transfers some cantharidin to her in his sperm packet, and she coats her eggs with it to protect them from predators.

In many insect species with predatory/parasitic larvae, Mom delivers the eggs to their eventual host, but Meloe beetle larvae are on their own. When they hatch, the super-active larvae, called triungulins, climb up onto flower heads and wait for bees to come along. Each species of Meloe beetle targets a particular genus or species of solitary, ground-nesting bee, and when the right one comes along, the larva jumps on.

Some sources say that the larva targets males, riding with him until he has a liaison with a female, and then switching to her. Other sources say that it ignores males and only attaches to females. The ultimate goal is access to the female’s nest, where it acts as a kleptoparasite, eating the food cache she has put by for her young (and sometimes eating her eggs, too). After it has gained entry to its host’s nest, the rest of its larval life is sedentary.

Oil beetles are usually seen moving slowly along the ground or on low vegetation. Adults feed on plant material, including pollen, nectar, and leaves.

Despite the toxicity of cantharidin, these beetles have been used in traditional medicines in East Asia, especially China, to treat external conditions like boils, warts, bruises, and fungal skin infections, and internally for cancer, liver issues, colds, and to induce abortions.

According to the Montana Natural History Center website, “For their diverse uses and fascinating ecology, oil beetles were named the 2020 insect of the year by an entomological society in Europe.”

Bugguide.net says that there are 22 species in the genus Meloe in North America, and the BugLady isn’t quite sure which species she found. Some are primarily active in spring and others in fall, but some may be found in both seasons, depending on the phenology of their host bees. Fall candidates in Wisconsin include:

- The Impressive oil beetle (Meloe impressus), about which the Minnesota Seasons website says “The first stage (triungulin) is mobile on plants. The entire hatched group climbs to the top of a plant and forms a cluster in roughly the shape of a female ground bee. It then exudes a chemical scent that mimics the pheromone of a female bee. When a male bee attempts to mate with the mass, some of the larvae attach themselves to its hairs. When the male mates with a female bee some of the larvae attach to the female. These remain on the female while she builds a nest, then detach and begin feeding on newly laid bee eggs.”

- The American/Buttercup oil beetle (Meloe americanus), which lays its eggs near the base of a flower (bugguide says that females of these first two species are hard to tell apart).

- The Short-winged blister beetle (Meloe campanicollis), which may persist into late fall.

- And Meloe exiguus (no common name), about which the BugLady could find nothing.

And when she put her pictures up on the monitor and looked closer? Besides seeing a lot of green frass (bug poop), the BugLady saw that one female was being bothered by some exceedingly small biting midges (family Ceratopogonidae). She sent the pictures to PJ Liesch (“the Wisconsin Bug Guy”), Director of the UW Madison Insect Diagnostic Lab, who shared some papers with her about a genus of biting midges (Atrichopogon) that have been associated with Meloe and other blister beetles (and shared her delight at the awesome experience). Thanks, PJ. The 16 Atrichopogon species that feed on the haemolymph of blister beetles have aptly been placed in a subgenus named Meloehelea. Atrichopogon levis, aka “the grass punky” https://bugguide.net/node/view/1151920/bgimage, is a likely suspect.

Go outside – look for bugs – look closely.

Kate Redmond, The BugLady

Bug of the Week archives:

http://uwm.edu/field-station/category/bug-of-the-week/