by Kate Redmond

Dogwood Scurfy Scale

Howdy, BugFans,

If asked to describe a Red-osier dogwood shrub, lots of people would say “it has red bark with white lumps on it.” It does – but it doesn’t.

Some of our most un-bug-like bugs are the scale insects. There are lots of them worldwide – about 8,400 species in 36 families. They’re called scales because they (the females, anyway) cling, limpet-like, to their food plant, protected under a waxy covering that looks fish-scale-ish. They’re sexually dimorphic (“two forms”), and adult males – in the species where males exist – are often tiny and gnat-like. If your basic definition of an insect is “six legs, some wings, and three body parts that are divided in segments” you’ll have to suspend it a bit for the scales.

Their nearest relatives are aphids, whiteflies, jumping plant lice, and phylloxera bugs.

They hatch from eggs that the female lays under her body (or they are viviparous – popped out “live”), sometimes fertilized with the help of a male and sometimes produced by parthenogenesis (“virgin birth”), and a very few species are hermaphroditic (they have dual equipment and can self-fertilize, and so a single individual can create a whole population). Six-legged when they hatch, scales enjoy two short, mobile instars (they’re called “crawlers”), during which they disperse, but their legs are short, so they don’t go far without help (crawlers may also be blown around by the wind). Then the tiny females settle down, attach to a host, and lose their legs, generally staying put for the rest of their lives. The short-lived males must find females where they sit, and although he may be winged, his wings are not good for much, so he comes on foot. There are generally several generations per year.

Scales are vegetarians, feeding on plant sap that they suck from leaves or branches. Some are found only on specific hosts and others are more generalist feeders, and although a very few species feed on mosses, lichens, and algae, as a group, they’re fond of the woody plants. Their predators include some ladybugs and lacewings, and a few parasitoid wasps whose larvae consume the insect (they target younger scales) or the eggs under the scale. There are scale insects that are serious plant pests, scale insects that are used to control invasive plants, and scale insects that are “cultivated” because they’re used to produce shellacs, waxes, and red dyes.

The two, big divisions of scale insects are “cushiony” and “armored” scales. Cushiony scales tend to be lumpier than armored scales, and they’re permanently attached to their waxy covering. The excess sap that they consume, released as a sweet fluid called “honeydew,” attracts other insects to feed on it, and some species of scale are cared for by ants that protect the scales from predators, harvest the honeydew, and help the crawlers find fresh twigs. The downside of honeydew is that sooty mold grows on leaves where its sticky sweetness falls, which interferes with photosynthesis and isn’t very wholesome looking. A species of cottony scale was featured in a BOTW years ago https://uwm.edu/field-station/bug-of-the-week/cottony-scale-family-coccidae/

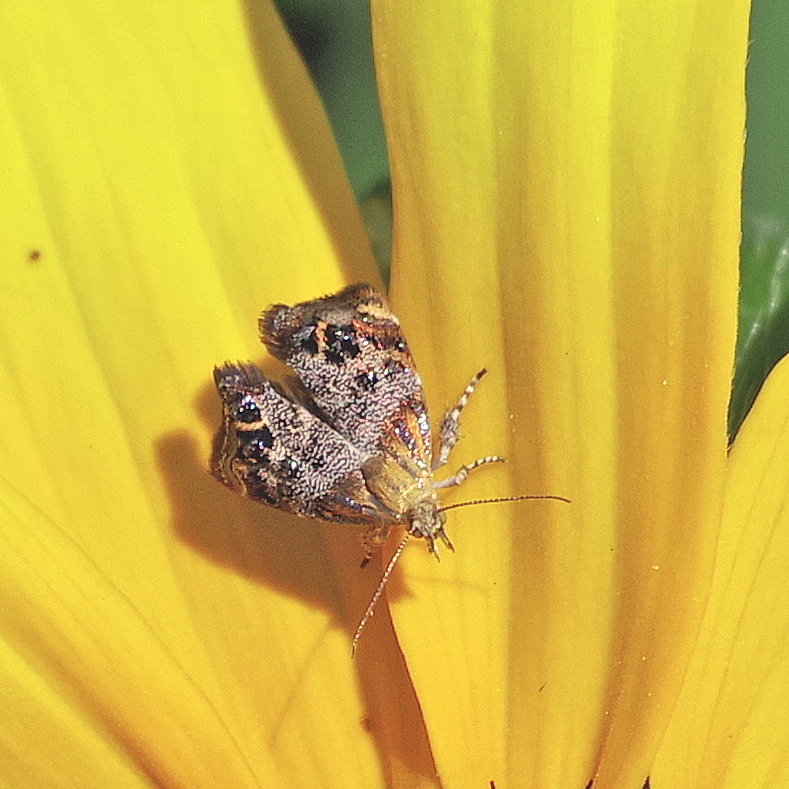

Dogwood scurfy scales are armored scales, and armored scales are in the family Diaspididae, the largest scale family (2650 species). Armored scales feed on hosts from 180 plant families. They’re not attached to their waxy cover, are smaller and flatter than cottony scales, and they don’t produce honeydew. Their tough – armored- coverings may be round, elliptical, or oyster shell-shaped and may have concentric rings/ridges. The female incorporates the shed skins from her crawler stage into her growing shell, and the wax is made and shaped by a structure called the pygidium at the rear of the abdomen. The critter below the scale has knob-like antennae, no legs, and little distinction between head and thorax.

Not surprisingly, with so many species of armored scales, there are many different lifestyles. In general, she lays her eggs or live young under her scale, which has a slit at the rear that allows them to exit. Her eggs overwinter under the shelter of her scale, though she’s no longer alive when they hatch.

The BugLady saw a paper that said that some armored scales may get around by phoresy – hitchhiking – sticking to their six-legged taxi cabs (the study identified a fly, a ladybug, and an ant) with the help of a few “suction-cup”-tipped hairs on each of their legs

FUN FACT ABOUT ANT PARTNERSHIPS

An odd relationship has evolved between a species of African ant and a species of armored scale (which, remember, have no honeydew to trade for ant favors). The ants shelter the scales in the galleries/tunnels they live in under tree bark – the ants are so specialized that they spend their whole lives there. The scales no longer need protection from the elements or from predators, so most of them are “naked,” though some still make wax and other scale-building materials that the ants eat along with the crawlers’ shed skins and various scale “excretions.” The whole thing hinges on the ant queen finding a suitable host tree and rounding up crawler-aged scales during her brief nuptial flight.

As the poet Muriel Rukeyser once said, “The world is made of stories, not atoms.”

SCURFY DOGWOOD SCALE/RED-OSIER SCALE INSECT

The BugLady started nibbling around the edges of this episode at least three years ago and hit a brick wall pretty fast. The Extension and Horticultural sites mostly said – “Yup, dogwoods get scales” but offered no names or biographies, so, the original iteration of this BOTW was something like, “These are dogwood scurfy scales – they’re everywhere, but no one’s written anything about them – thanks as always to PJ at the Insect Diagnostic Lab in Madison for pointing the BugLady toward an ID.”

But the BugLady could never do that, so…..

In her initial search for a name, the BugLady came across the pine leaf scale (Chionaspis pinifoliae https://bugguide.net/node/view/361628/bgimage) that looked similar, but she thought it was unlikely to be her scale because, well, pine needles. The dogwood scale suggested by PJ is Chionaspis corni; in the same genus, but when you Google Chionaspis corni, most hits are for Chionaspis pinifoliae. Bugguide.net lists no other genus members and although the dogwood scurfy scale is common here, does not even show the genus as occurring in Wisconsin (buggide’s caveat about its range maps is “The information below is based on images submitted and identified by contributors. Range and date information may be incomplete, overinclusive, or just plain wrong”).

Just to make things interesting, the accepted spelling of the genus name (since 1868) is Chionaspis, but over the years it has officially been misspelled by later taxonomists as Chianaspis, Chiomaspis, and Chionapsis.

The BugLady checked the wonderful Illinois Wildflowers website https://www.illinoiswildflowers.info/ and found the dogwood scale (along with several other species of scale including the willow scale and the Gloomy scale) mentioned in the Faunal Associations sections of the write-ups of red-osier and flowering dogwoods and several other dogwood shrubs.

And one more thing – “scurfy” means rough or scaly or covered with scurf, and a “scurf” is a flake, scale or dandruff.

Whew!

Kate Redmond, The BugLady

Bug of the Week archives:

http://uwm.edu/field-station/category/bug-of-the-week/