by Kate Redmond

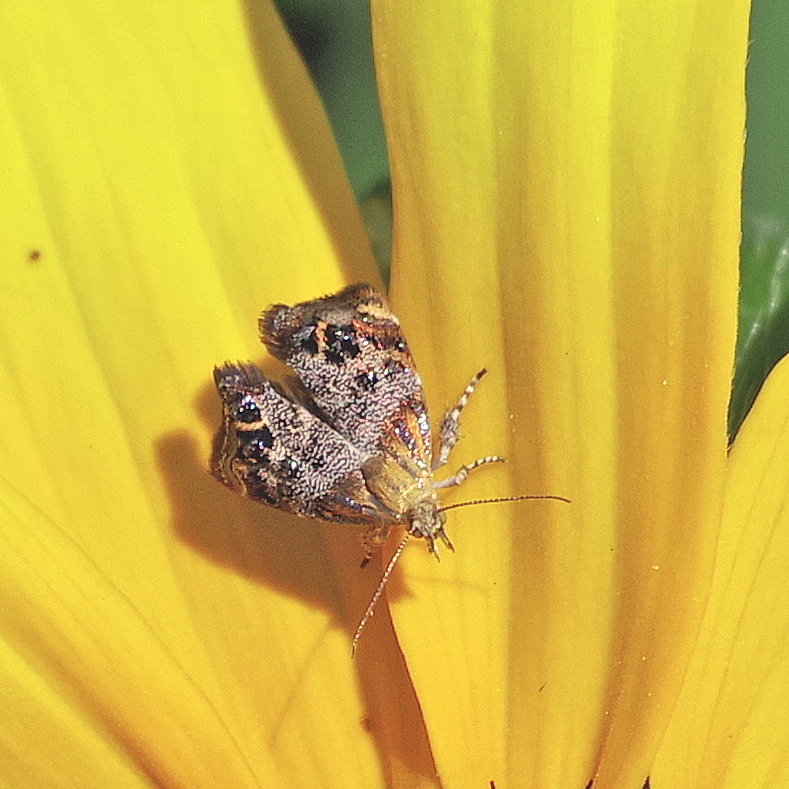

Rosinweed Moth

Howdy, BugFans,

First off, today’s vocabulary word is “microlep” (short for “microlepidoptera”). What’s a microlep? The (somewhat squishy) term applies to moths with a wingspan under 20mm (about ¾”). It’s not a taxonomic or a lifestyle designation – there are microleps across a bunch of different moth families, and they make their livings in a variety of ways – it’s strictly about size.

Rosinweed moths (Tebenna silphiella) (what a little gem!) are a not-well-studied species in a not-well-studied genus in a not-well-studied family, Choreutidae, the Metalmark Moths, a group that (of course) needs revision and that historically has been bounced around, taxonomically. And, the website microleps.org tells us that “The large Tebenna spp., including T. silphiella, represent an array in which species delineations appear to be unresolved.” Most family members have wingspans under a half-inch, but those wings may be decorated with spots made of silvery/metallic scales https://bugguide.net/node/view/1169370/bgpage, https://bugguide.net/node/view/1681270/bgimage. Choreutis comes from a Greek word meaning “dancer” – the moths fly by day, and the “dancing” refers to the jerky movements they often make with their bodies and wings as they move around on flowers.

Choreutid caterpillars skeletonize the undersides of leaves in groups, immediately after hatching, and solo, as they get older. Many species spin a loose web over themselves, and their frass collects in this net (remember – they’re under the leaf). About caterpillars in the related genus Brenthia (a mostly Asian and African genus), researcher Jadranka Rota says “Larvae of all four Brenthia species that I have observed chew a roughly circular ‘escape hatch’ – a wormhole – somewhere in their feeding shelter. When resting, they sit with their head next to the hole. If disturbed, larvae dash through the wormhole to the other side of the leaf…… After a little while, they wriggle through the opening backwards to their original position.” Another researcher hypothesizes that the caterpillars receive sensory clues via the webbing.

Some Metalmark moths have a Superpower – more about that in a sec.

As the name suggests, the host plant of Rosinweed moths is Rosinweed (Silphium integrifolium), a prairie plant with stiff, gritty leaves https://illinoiswildflowers.info/prairie/plantx/rosinweedx.htm. They feed on leaves near the top of the plant; scroll down for a picture of caterpillars feeding https://mothphotographersgroup.msstate.edu/species.php?hodges=2642.

Bugguide.net lists the range of Rosinweed moths as the prairies and meadows of the Central US – Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, Arkansas, and Kentucky, and other sources add Colorado. There are two generations per year.

OK – the Superpower.

In many parts of the family’s worldwide range, their top predators are the jumping spiders that hang out on the leaves with them. What’s a moth to do? Answer – If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.

Jumping spiders hone in on a wide variety of prey, large and small, and they’re not shy about eating other jumping spiders, no matter the size, so mimicking a jumping spider certainly isn’t a Get Out of Jail Free card. But it turns out that the spots and stripes on the wings of many Metalmark moths resemble a jumping spider (if you squint), and the moth’s posture, displays, and movements reinforce that. In experiments, Brentia moths survived being caged with jumping spiders more often than similarly-sized, non-Choreutid moths did (unless researchers painted over the eyespots on their wings). Often, the jumping spiders (even with their great eyesight) would respond to the moth’s antics with the kinds of leg-waving territorial displays that they reserve for other jumping spiders of the same species. If the moth was bigger than the spider, the spider may even have been intimidated by the moth.

Here’s an American Brenthia, the Peacock Brenthia https://bugguide.net/node/view/1801949/bgimage and a video of a Metalmark moth in action – https://www.reddit.com/r/Awwducational/comments/ryq98f/metalmark_moths_have_evolved_eyespots_on_their/?rdt=48206.

Researchers also suspect that looking like a jumping spider discourages some of the spiders’ predators from going after the moths. Some species hide by camouflage or by mimicking species that are aggressive or toxic. Metalmark moths confuse the spider with an uncommon, “In your face” strategy called “predator mimicry,” but it turns out that jumping spider mimicry is also in the playbooks of a few small flies and planthoppers, which suggests that the spiders are driving the evolution of their prey.

For more information see https://askabiologist.asu.edu/plosable/prey-as-predator.

Kate Redmond, The BugLady

Bug of the Week archives:

http://uwm.edu/field-station/category/bug-of-the-week/